▶ Watch Video: Severe weather and climate disasters cost $165 billion in the U.S. in 2022, NOAA says

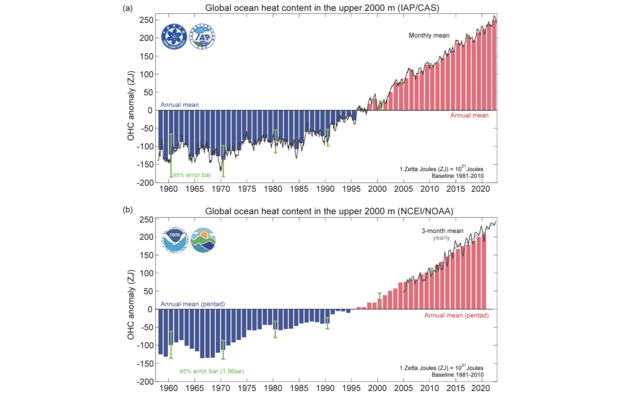

During World War II, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan, wiping out 90% of the city. Last year, researchers say, the ocean heated up an amount equal to the energy of five of those bombs detonating underwater “every second for 24 hours a day for the entire year.”

John Abraham, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, is among more than a dozen scientists who revealed this week the ocean in 2022 was “the hottest ever recorded by humans.” It increased by 10.9 Zetta Joules, an amount of energy equivalent to the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima and an amount of heat about 100 times more than the electricity generated worldwide in 2021.

Four basins of the seven world ocean regions – the North Pacific, North Atlantic, Mediterranean and southern oceans – had the highest heat records since the 1950s.

This marks the fourth time in a row that ocean heat content has surpassed records broken the year prior. And while it may seem like a “broken record” at this point, Abraham said this is anything but “normal.”

“This is a continuing, ongoing trend,” he said. “It’s getting worse every year.”

Here’s what the findings, published in the Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, mean for the current state of the planet, and the future.

More fuel for extreme weather

Ken Caldeira, a climate scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science as well as a senior scientist at Breakthrough Energy, told CBS News that the ocean “is the pacemaker of the climate systems response to our CO2 emissions.”

“The amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is increasing year by year. And these greenhouse gases, trap energy in Earth’s system prevent it from going to space, and most of that energy goes into the ocean, which causes the ocean to warm,” he said.

From there, some of the ocean heat is transferred back to the atmosphere, Abraham said, as is moisture and humidity, creating a surge of more energy that “makes storms more powerful.”

“So when oceans warm and when the Earth warms, it makes our weather wilder,” Abraham said. “We go from one extreme to the other, more rapidly.”

The most recent example of this can be seen in California, which has undergone weeks of heavy flooding and record-breaking rain as a series of atmospheric rivers barrage the West Coast. Climate change didn’t cause those atmospheric rivers and storms, but a warmer atmosphere has been linked to making storms more intense.

Oceans are facing another problem. When it rains, the fresh water from the clouds helps decrease salinity in the ocean as new water comes down. But data shows that rain isn’t providing equal coverage across the seas, with areas that typically get a lot of rain experiencing even more in the past year, reducing their salinity. Meanwhile those in usually dry environments become even drier, increasing those levels as more water evaporates than comes down.

Because of this, the salinity-contrast index – essentially the difference between the highest and lowest salinity levels in the upper 2,000 meters of the ocean – also reached its highest level on record last year.

A high salinity-contrast index and high ocean temperatures can individually make weather events more severe.

“And they are now conspiring together,” Abraham told CBS News. “Their effects are additive.”

Ocean regulation has become “problematic”

The increasing measures of temperature and salinity have also led to another issue within the ocean – it’s ability to self-regulate. Water usually experiences vertical mixing, in which water from the top carries valuable gases and heat to the bottom of the ocean while water from the bottom moves up, carrying with it vital nutrients.

The latest study explains that this process is “a central element of Earth’s climate system.” But since 1960, researchers estimate that stratifcation, or the separation of water layers that makes this process more difficult, has increased by 5.3% in the upper 2,000 meters of the ocean and up to about four times that amount in the upper 150 meters.

“What we’ve discovered is mixing is happening less,” Abraham said. “…Because of climate change and because we’ve heated the surface waters so much, they aren’t able to fall downwards … And that is problematic.”

That’s because if heat from the surface can’t mix with the cooler water below, that surface will only get warmer and reduce how much carbon the water can store – an ability that is vital to extending the global warming process. The ocean is like a sponge for carbon emissions, taking in about 90% of the heat from the worldwide total, but if its ability to do so is diminishing as emissions are only increasing, experts say the planet will only warm faster, making the worst impacts of climate change happen sooner.

Investing in climate solutions a “no brainer”

All of this data gathered leads Abraham to believe that “we will never hit the Paris Accord goals” of keeping global warming within 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. Even the United Nations has said that the world is more on track to hit nearly 3 degrees Celsius by the time today’s children are grandparents.

We can’t undo the damage that has already been done, Caldeira said, but we can prevent it from getting worse.

“Right now, our carbon dioxide emissions from our energy system are around 100 times bigger than all of the carbon dioxide emissions from every volcano and mid-ocean ridge and geothermal vents and everything that exists in nature,” he said. “…The most important thing we can do is transition to an energy system that doesn’t use the atmosphere and the oceans as a waste dump.”

“We can solve this problem today with today’s technology, we just need to get off your asses and start doing it,” Abraham added, saying that doing so “is a no brainer” when you consider the the exorbitant costs of climate disasters, which topped $165 billion in the U.S. alone last year.

The cost of green energy, for example, has substantially decreased in recent years, and in many cases, is now comparable or even cheaper to coal. Over the past decade, the cost to install solar panels has dropped more than 60%. And last year’s passage of the Inflation Reduction Act also created numerous opportunities for discounted home upgrades, electric vehicles and more.

“We’ve reached an economic tipping point where it’s starting to make economic sense to use clean energy,” Abraham said. “…Earth’s climate is a heavy locomotive. And if you want to stop a heavy locomotive, you’ve got to put the brakes on and it’ll take you like a mile to stop. … You’ve got to start taking actions early and give it time give time for those actions to have measurable outcomes.”